“How’s the Copilot rollout going?” your EVP asks during your quarterly review.

“Usage is steady,” you reply. “We’re hovering around 80% of developers using it weekly.”

“That’s good, right?” she asks.

You pause. The number looks fine but you’ve been watching quality slip for weeks. More AI slop making it through review, developers accepting whatever comes back on the first try, the same prompts copy-pasted without anyone thinking about whether they actually work.

“The usage number is fine,” you say carefully. “But I’m more concerned about how they’re using it.”

If you’re leading AI tool adoption for developers, whether it’s Copilot, Cursor, or something else, you’ve probably figured this out already. Getting developers to try the tool is easy but getting them to use it well, consistently, over time is where it gets hard.

After leading Copilot adoption for a few hundred engineers, here’s what I learned: the work doesn’t end at rollout. That’s where it starts.

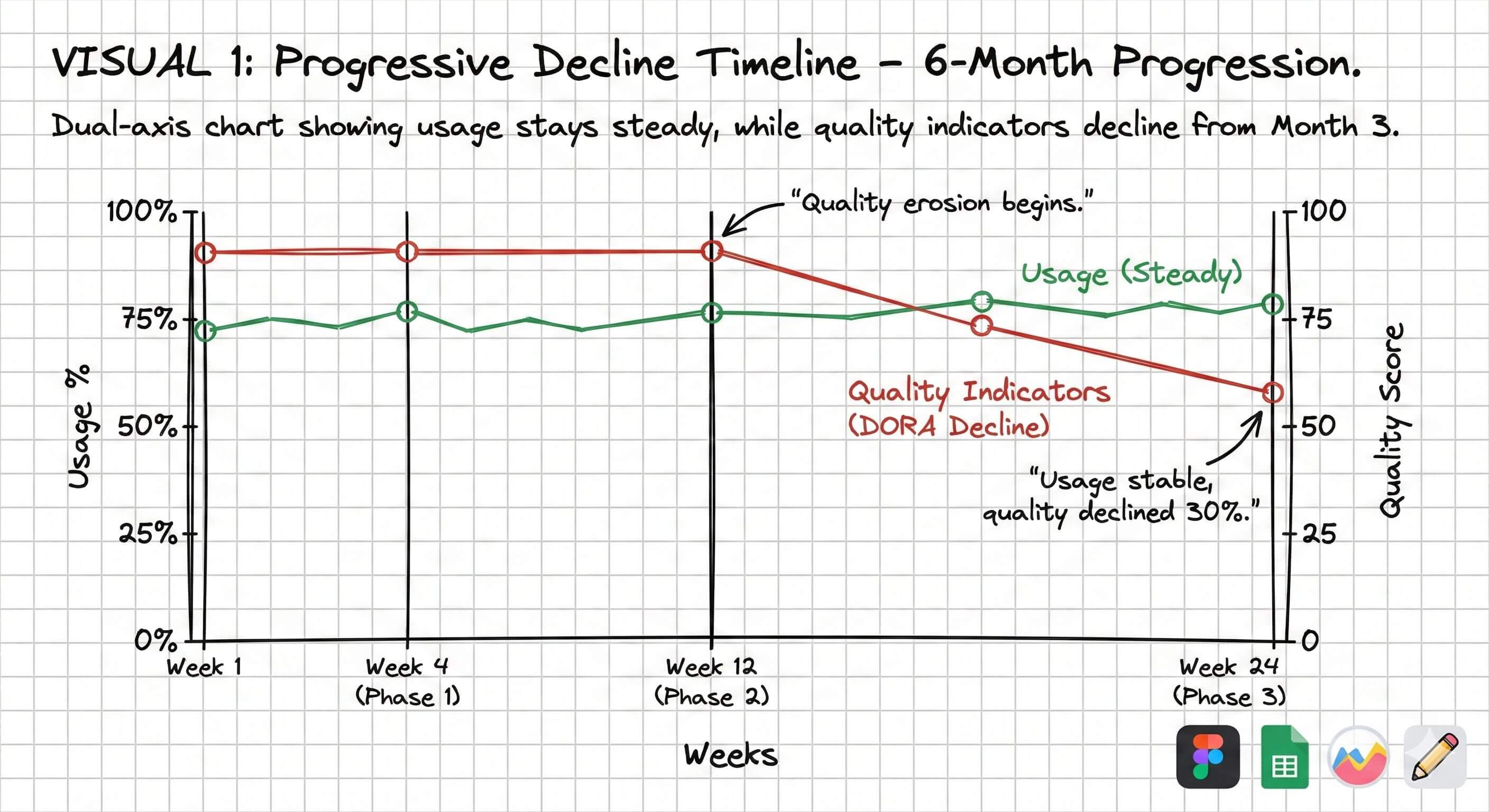

The Pattern You’ve Probably Seen: Progressive Decline

Let me describe what typically happens with AI coding tool adoption.

Developers try GitHub Copilot or Cursor or whatever tool you’ve chosen. There are some early wins, a lot of excitement in Slack and during demos. Soon usage patterns start to emerge, some developers integrate it deeply into their workflow and others use it occasionally. All of them usually struggle with writing good prompts.

Developers start accepting AI’s first output without iteration. Large AI-generated PRs appear with minimal context. Code review quality declines because reviewers assume AI code is good.

Around month 3 we started noticing it in code reviews. PRs with 300 lines of AI-generated code and one-line descriptions, prompts like “make this better” with no context, nobody iterating anymore. They’d take the first output and ship it. The slop crept in while reviewers waved it through because they assumed AI code was probably fine.

Usage numbers might look stable but the quality has degraded, MTTR has increased, and frequency of errors is way higher than it should be. The tool has become a crutch rather than an amplifier and by this point it’s hard to reverse because the habits are set.

Where Most Adoption Strategies Go Wrong

Most organizations approach this like a product launch: choose a tool, get licenses, roll out access, run training, track usage, and declare success when numbers look good.

That treats adoption as an event, something you do once and check off the list, but it’s more like a capability you build over time. We learned that the hard way.

Event thinking says: “80% of developers used Copilot this month.” Capability thinking asks: are those developers generating code they actually understand? Are they iterating on prompts or just accepting first outputs? Is quality holding up?

Our launch went fine but the real work was everything that came after and we weren’t ready for it.

The Problems We Faced

Quality Eroded As Developers Used Copilot More Everyday

Early adoption metrics looked good with 70-80% usage, but developers were accepting AI’s first output without iteration.

They’d describe a problem to Copilot, get code back, glance at it, and submit a PR with no refinement, no questioning, and no iteration.

We got code that technically worked but was overly complex with patterns that didn’t match our codebase, missing error handling, and subtle bugs that showed up days later when someone else touched the code.

Initial adopters were thoughtful, they iterated on prompts, reviewed AI output critically, and tested thoroughly. But as adoption spread those practices didn’t transfer.

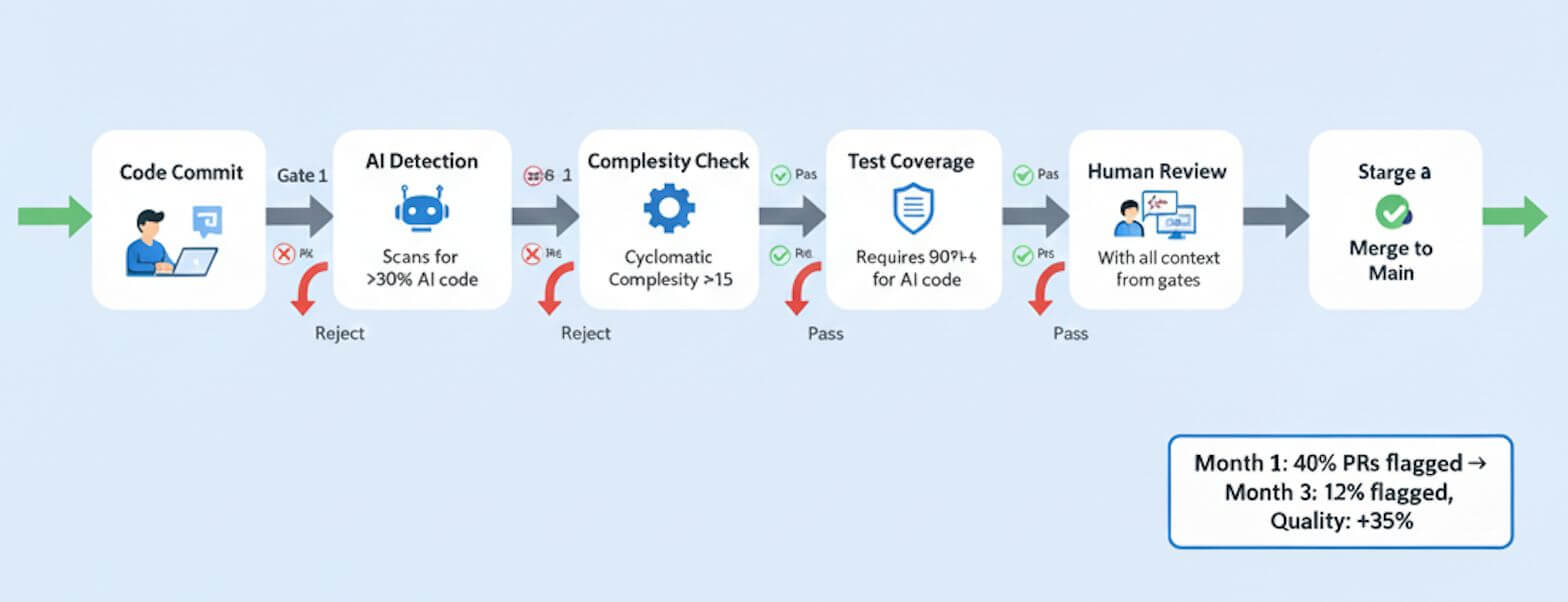

Solution: Better CI/CD Gates

We added automated gates to the pipeline. PRs with more than 30% AI-generated code got flagged for extra review, overly complex AI-generated functions got rejected outright, tests were required for AI code, and if AI wrote it you had to explain what it did in the PR description.

Prompting Is a Skill (Most Engineers Are Bad At It)

Effective prompting is a skill and we had excellent engineers who were terrible prompters. Bad prompts looked like “Make this code better” with no criteria for what better meant, or “Fix this bug, logs in terminal” with zero context about what the bug was, or dumping 500 lines with “optimize this”.

Engineers got frustrated and “Copilot doesn’t work for me” almost always meant “I don’t know how to prompt.” We didn’t realize that early enough.

Tool training isn’t enough, you need continuous prompting skill development and we underestimated this badly.

Solution: Context Integration (MCP Servers) and Prompt Repository

We built MCP servers that gave AI access to our JIRA tickets, Confluence docs, internal API documentation, and code style guides.

We ran multiple Show and Tell sessions focused on prompt engineering. Every team contributed to a shared prompt repository, adding their best practices and useful examples over time. It became a simple way for everyone to learn from each other and pick up patterns that were working well across the org.

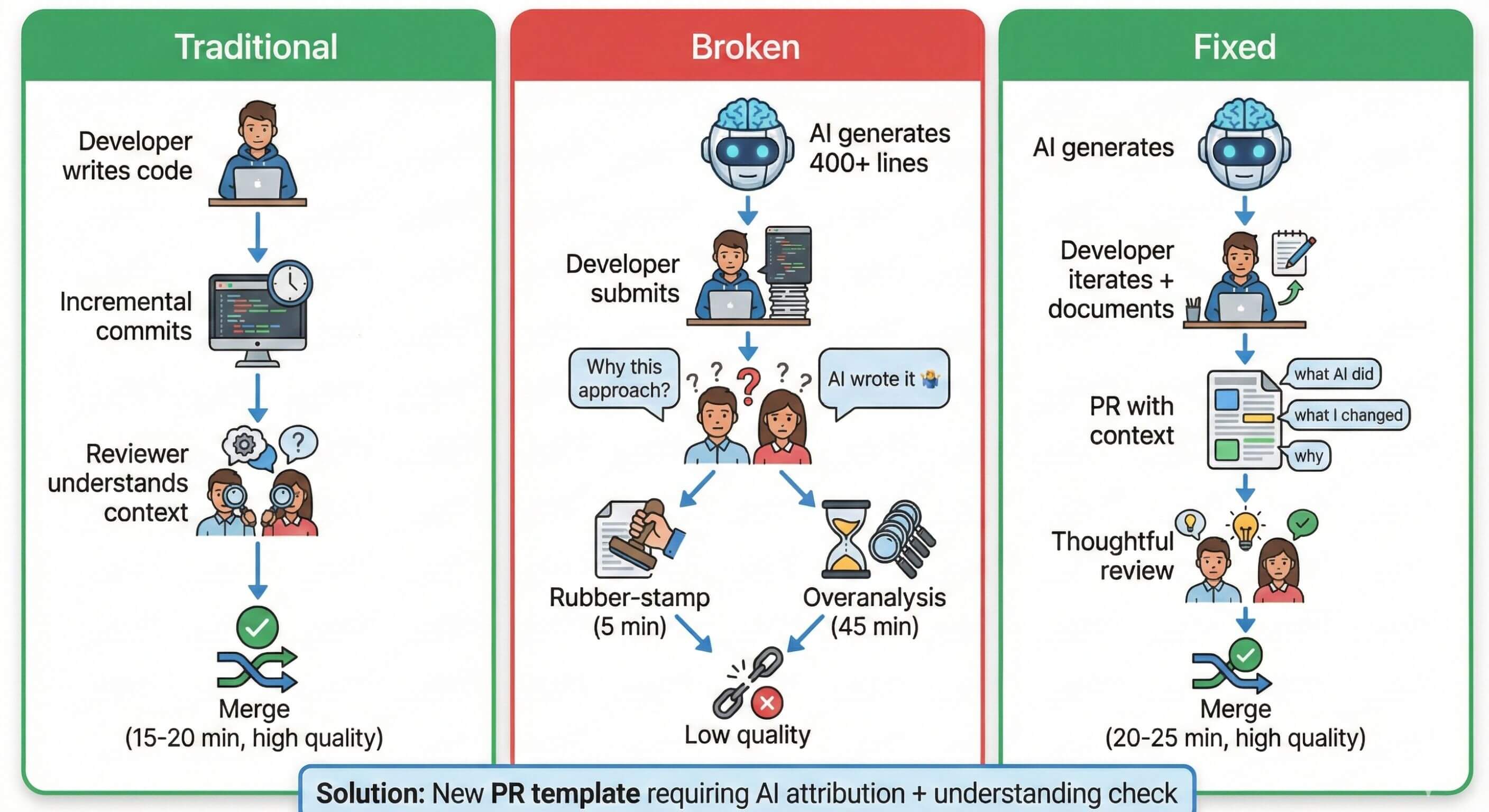

Long PRs

One of the biggest problems was large AI-generated PRs. Developers would ask AI to implement entire features resulting in 400+ line PRs that were impossible to review properly.

Solution: breaking down work at two levels.

At the PM level: write user stories that are small and focused where each story should be implementable in 200 lines or less with acceptance criteria specific enough that AI doesn’t over-engineer. At the developer level: break implementation into smaller chunks, use AI for one piece at a time instead of the entire feature, and make sure each PR has a single clear purpose.

At the developer level break implementation into smaller chunks, use AI for one piece at a time instead of the entire feature, and make sure each PR has a single clear purpose.

When PMs write tight stories, developers naturally create smaller PRs. We had to change how we planned work, not just how we coded, and that took longer to figure out than I’d like to admit.

The Sustainability Problem

If you can submit AI-generated code without explaining it, some developers will. If you can skip testing and it passes review anyway, some developers will. If lazy prompts produce acceptable output, people will keep using lazy prompts.

Solution

The path of least resistance was using AI carelessly and we needed to flip that. Make it easier to use AI well than to use it badly, which meant changing defaults, and address this as a cultural problem.

Our “AI Champion” group was given 20% dedicated time for the program. There’d monthly syncs, regular retros across teams on issues caused by AI generated code, multiple org-wide tech sessions on best practices and discussions on Sev 1 issues. Making AI expertise count toward promotion also helped maintain good practices.

For ongoing learning we added weekly “AI Office Hours” where people brought real code they were stuck on, and a monthly “AI Lunch” with casual discussion and no slides. That last one turned out to be where some of the best conversations happened.

The Measurement Problem

Every exec wanted to know if we were more productive and I didn’t have a good answer then. Still don’t have a clean one now, if I’m honest.

Building comprehensive productivity measurement would have required 6+ months of data engineering, dashboard infrastructure we didn’t have, instrumentation across multiple tools, and a team to maintain it. We didn’t have those resources so we focused on adoption and quality signals instead of productivity metrics.

Our reasoning was: if developers aren’t using the tool then productivity doesn’t matter, if they’re using it badly then productivity gains are illusory, and if they’re using it well then improvements will show over time. PR lead time gives us a rough proxy without perfect measurement. Not ideal but it worked well enough.

We gave up on perfect productivity measurement. Our dashboard was simple: weekly active users by tool, adoption by team, PR lead time trend on a 6-week rolling average, and self-reported “AI made me faster this week” sentiment.

That covered quality and culture. But execs still wanted numbers.

What I’d Do Differently

If I ran this again, I’d focus on guardrails before capabilities. We spent too much time showing what AI could do and not enough on what good AI-assisted review looks like. Should’ve been the other way around.

I’d also build context integration before launch, not after. Generic AI is cool for demos but it’s not that useful for real work. MCP servers connecting to your actual codebase, your actual tickets, that’s what makes the difference. We figured this out late.

And I’d rotate champions every 3 months from the start. We waited too long and burned out our best advocates. The biggest miss was treating lazy usage as a tooling problem, it’s a culture problem. Your adoption team needs to keep hammering that message until it sticks with the wider team. We didn’t do enough of that.

What Success Actually Looks Like

Good signs look like this: developers iterating on prompts instead of accepting first output, AI-assisted PRs that actually explain what was generated versus what was modified, code review discussions that focus on design not just catching syntax issues, and quality metrics staying stable or even improving. When you see these you’re probably on the right track.

Warning signs are: PR size creeping up without good reason, code review becoming a rubber stamp, developers who can’t explain code they submitted, bug rates going up in AI-assisted code, and prompts getting lazier over time. If you’re seeing these then usage numbers don’t matter because you have a quality problem.

The metric that matters most isn’t ”% of developers using AI,” it’s quality of AI-generated code over time. If usage is high but quality is declining, that’s not success, that’s a problem you need to fix before it gets worse.