Every engineering team has help channels. Slack channels, ServiceNow tickets, internal forums. Places where people go when they’re stuck.

And every team has that person, the one who posts “it’s broken, help” and then disappears for three hours. The one whose questions generate more questions than answers. The one who makes your best engineers mute the channel. We had dozens of them.

We were losing business because our engineers couldn’t ask for help effectively. Not because they weren’t smart or weren’t trying, but because when they got stuck their help requests looked like this:

Jenkins pipeline broken. Need help ASAP.

Or this:

Getting an error when I run the deploy script. Can someone help?

The person trying to help would spend 20 minutes pulling teeth before they could even start solving the actual problem. Which environment? What error? What did you try?

Our client-side teams started complaining. “Your India team doesn’t communicate well.” Tickets sat unresolved. Slack channels became graveyards of unanswered questions. And the engineers who actually knew how to ask good questions were drowning in requests from those who didn’t.

The real cost wasn’t just time, it was trust and credibility. The kind of reputation damage that loses contracts. So we built a framework, made it mandatory, and held people accountable.

Why Telling to “Communicate Better” Doesn’t Work

We tried fixing this the way most companies do. We sent emails and started talking about it in our team meetings. People nodded but nothing changed, we kept hearing complaints from our clients.

We even tried calling people out gently in the thread. “Hey, can you provide more details?” That just led to five more messages of back-and-forth before we could even understand the problem.

The issue wasn’t that people didn’t want to communicate well. It was that nobody had taught them what “good” actually looked like.

Think about it, these engineers learned to code by reading Stack Overflow answers and documentation. They’d never learned to ask questions.

So we did what engineers do. We built a system. Why hadn’t anyone done this before?

The System: Right Way to Ask for Help

The system has two parts. First you do your homework and actually try to solve the problem yourself. Second, when you do ask, you structure your request so someone can help you immediately.

Most people skip the first part entirely. They hit a problem and immediately reach for the help channel, which is why their questions are vague. They haven’t done the work to understand their own problem yet.

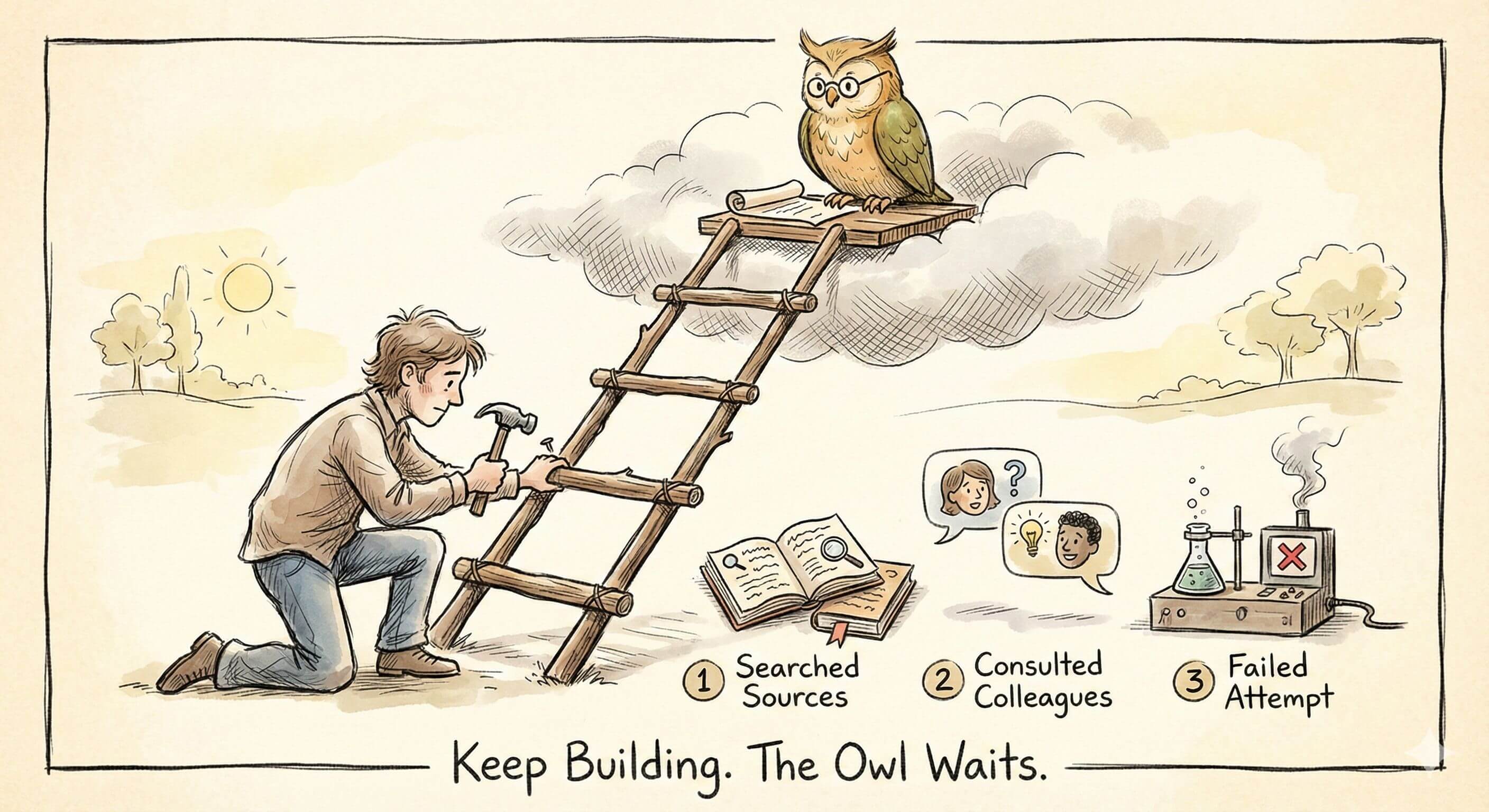

Part 1: Before You Ask: The 3-2-1 Rule

Don’t ask for help until you’ve searched at least three sources (internal wiki, Slack history using search modifiers, Google or Stack Overflow), asked at least two peers (a quick DM to a colleague, a sanity check in your team channel), and tried at least one solution yourself while capturing what happened in logs or error messages.

If you haven’t done 3-2-1, you’re not ready to ask for help.

This isn’t busywork, it’s respect. When someone takes time to help you, the least you can do is show you’ve tried.

Even after engineers started following the 3-2-1 Rule we still had a problem. Their messages would turn out like this:

I checked the wiki and talked to Sarah and tried changing the config but it’s still not working. The logs say something about auth. I need to deploy by EOD.

They had everything we asked for but it was buried in a wall of text. The helper still couldn’t tell where to start. So we added structure.

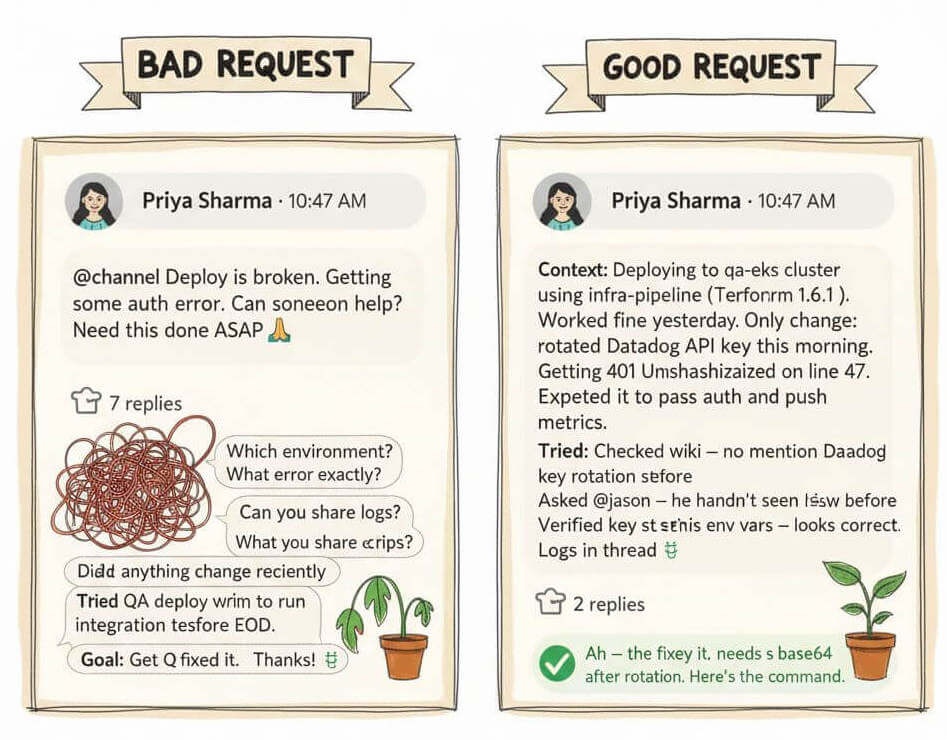

Part 2: When You Ask: The Context→Problem→Goal Framing

Every help request should follow this structure:

Context sets the scene. Where are you? What are you working on? What changed recently? Include the environment (staging/prod/local), tool versions (“Terraform 1.6.1, AWS Lambda Node 18”), recent changes (“upgraded the provider yesterday”), and links to tickets or dashboards.

A good context looks like:

Trying to deploy to our QA EKS cluster using the infra-as-code pipeline. This worked last week. Only change is a new IAM role added yesterday.

A bad context looks like: “Terraform pipeline are failing. Could anyone help?”

Problem describes what’s actually going wrong. Be specific and report symptoms, not theories. Include what you expected to happen, what actually happened, relevant logs (1-3 lines formatted as code), and what you’ve already tried.

A good problem description:

Running make deploy hangs after the Datadog config step. Logs show 401 Unauthorized. I rotated the API key this morning, maybe that broke something?

Not so good:

“Deploy isn’t working. Probably Datadog or Jenkins.”

Goal explains what you’re trying to achieve. Don’t just describe the step you’re stuck on, explain the outcome you want. People might know a better path to your goal.

A Good goal:

“I’m trying to allow our QA Lambda to push metrics to Datadog.”

A bad goal:

Need to add a Terraform variable but don’t have permissions.

The difference is that the second request can be answered immediately while the first requires five follow-up questions.

The Anti-Patterns (What Not to Do)

Once we started teaching this we also had to teach what not to do, because some patterns were so common they needed explicit callouts.

Don’t post screenshots of code or logs unless you’re reporting a UI bug. Screenshots can’t be searched so future teammates won’t find your post, they can’t be copied so people have to retype errors, and they’re hard to read because they get compressed and blurred. Use code blocks instead.

Don’t ask homework questions in help channels. Help channels are for blockers, not learning exercises. If it’s a problem you’re meant to struggle through like training or tutorials, ask your immediate team or peers, not a channel with 200 people.

Don’t dump 300 lines of logs and hope someone figures it out. Keep it tight: 3-4 sentences, one code snippet under 10 lines, one log excerpt. Use threads for additional details.

Don’t bury the problem. Don’t write a 20-line message with your actual question hidden in the middle. Lead with the problem and put context in threads if needed.

Making It Stick

Some people will say this feels like micromanagement. I’d argue the opposite, vague expectations are what’s actually unfair. Guidelines without enforcement are just suggestions that everyone ignores.

We didn’t just create the framework, we made it mandatory unless you have a time crunch or dealing with a production issue.

We created a training module for all and made it part of onboarding process.

We briefly set up governance calls. Fortnightly calls with team leads where we reviewed real messages from Slack and ServiceNow, audited patterns and flagged violations. We escalated if patterns continued.

What Changed

No, I’m not going to give you a “37% improvement in resolution time” metric.

The questions got better and you could see it immediately in Slack. Requests started showing up with clear context, evidence of self-help, and properly formatted code blocks. The back-and-forth dropped and what used to be 5+ messages became 1-2. Search numbers on Confluence shot up. When someone posted a well-structured question, three people would jump in to help within minutes. Someone replied “This is how it’s done” and that became the new normal.

The culture shifted. People started calling out good questions publicly: “This is a perfect ask.” It became social proof and the standard changed.

The complaints stopped. Client teams stopped escalating communication issues. Help channels became functional again. Engineers who’d been ignoring Slack started responding.

Further Reading

If you want to dive deeper into the philosophy behind this:

- How To Ask Questions The Smart Way by Eric Raymond (the classic, though dated)

- XY Problem - Why asking about your attempted solution doesn’t work

- Stack Overflow: How do I ask a good question?